We read a wide range of fiction and non-fiction, including novels, biographies, memoirs, poetry, short stories, and anthologies, and explore how these works relate to our individual practice and everyday life down in the market. This is a welcoming space for integrating dharma and lived experience through written art, less so a space for formalized dharma study. We meet on a monthly (ish) basis from January through September, and reserve October through December for the ango reading.

>>> email shoku @ shoku.cristina@gmail.com to get on the list for regular communications and last-minute updates. looking forward to reading with you!<<<

2026

JANUARY

Date: January 26, 6 PM – 7PM

Book: Kokoro by Natsume Soseki

Kokoro is a 1914 novel about a young student who becomes attached to an older man he calls Sensei. As their relationship deepens, the student senses that Sensei lives in quiet isolation and carries a serious moral burden. The story unfolds slowly, focusing on trust, distance, and misunderstanding, before turning to Sensei’s written confession, which reveals a past choice that shaped his loneliness. Set against the backdrop of Japan’s shift from traditional to modern values, the novel prepares the reader for an intimate exploration of guilt, responsibility, and the complexity of human relationships.

FEBRUARY

Date: February 23, 6PM – 7PM

Book: The Essential Rumi, translated by Coleman Barks

The Essential Rumi is a curated selection of poems by the 13th-century Persian poet and mystic Jalāl ad-Dīn Rumi, presented in contemporary English. The poems range from brief lyrics to longer meditations, addressing love, loss, longing, silence, and transformation. Rather than telling a single story, the collection introduces Rumi’s voice as one that repeatedly points beyond ordinary identity toward direct experience of the sacred. Readers can expect an emphasis on paradox, ecstatic imagery, and inward turning, with poems meant to be entered slowly rather than read linearly.

MARCH

Date: March 30, 6PM – 7PM

Book: Inspector Saito’s Small Satori by Janwillem Van De Wetering

Inspector Saitō’s Small Satori is a crime novel set in Japan that blends a straightforward murder investigation with Zen-inflected reflection. The story follows Inspector Saitō, a seasoned Tokyo detective whose method is shaped as much by quiet observation and self-discipline as by procedure. As the case unfolds, the novel lingers on routine, boredom, sudden insight, and the limits of rational explanation.

2025 READINGS

The Years of Rice and Salt by Kim Stanley Robinson

An alternate history epic spanning 700 years, imagining a world where the Black Death killed 99% of Europe’s population in the 14th century, leaving Islamic and Asian civilizations to dominate global history. The novel follows a group of reincarnated souls across multiple lifetimes – as soldiers, scientists, feminists, philosophers – through different cultures (Chinese, Islamic, Indian, Native American). It explores how scientific progress, religious reformation, and modernity might have unfolded without European dominance, examining themes of reincarnation, cultural exchange, war, and human progress. Dense, ambitious, philosophical historical fiction.

Tokyo Ueno Station by Yi Miri

A ghost of a homeless man haunts Tokyo’s Ueno Park, reflecting on his life. Born the same day as the Emperor, he left his rural village to work as a laborer in Tokyo, sending money home. After his son dies in an accident, his life unravels – he loses his wife, his purpose, and eventually becomes homeless, living among others in Ueno Park. The novel explores class divide, invisibility of the marginalized, loss, and the contrast between Imperial Japan and those left behind. Spare, haunting, and deeply moving.

The Sound of a Wild Snail Eating by Elisabeth Tova Bailey

A bedridden woman with a debilitating illness finds companionship and hope by observing a wild snail placed on her nightstand. Through watching this tiny creature’s daily life – including hearing it eat at night – she discovers profound lessons about resilience and the beauty of small things during her darkest time. It’s a short, meditative memoir about illness, nature, and finding wonder in the tiniest of lives.

The Lathe of Heaven, A Novel by Ursula K Le Guin

The Lathe of Heaven is a science fiction novel centered on a man whose dreams literally alter reality. When his condition is discovered by a well-intentioned psychiatrist, attempts to use these “effective dreams” to improve the world lead to increasingly distorted and unintended consequences. Set in a near-future Portland, the novel explores power, responsibility, and the limits of rational control. Readers should expect a quiet, unsettling story that treats reality as fragile and examines how even benevolent intentions can deepen suffering when imposed on the world.

In Love with the World: A Monk’s Journey Through the Bardos of Living and Dying by Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche

The book is a first-person account of Mingyur Rinpoche secretly leaving his monastery to undertake traditional wandering retreat, during which he nearly dies from illness. That lived experience becomes a practical exposition of the bardos—transitional states emphasized in Tibetan Buddhism—not as abstract post-mortem doctrines, but as ongoing processes present throughout life. Rinpoche uses his own near death experience to ground his writing.

How We Live is How We Die by Pema Chodron

Pema Chödrön’s How We Live is How We Die offers profound insights into the nature of life and death from a Buddhist perspective. As a lay Buddhist, I found her teachings deeply resonant and accessible. Chödrön’s approach emphasizes the importance of living fully in the present moment, embracing the impermanence of life with compassion and mindfulness. Her guidance on how our everyday actions and attitudes shape our experience of dying provides a comforting and practical framework for navigating both the ordinary and the extraordinary moments of our lives. The book’s blend of wisdom and simplicity makes it a valuable resource for anyone looking to understand how to live with greater awareness and ease.

Review by- SōShin YōSan/July 2024

Fire Monks: Zen Mind Meets Wildfire

/Colleen Morton Bush – Penguin Press

Whether you are getting ready to visit Tassajara for the first time, or you know it well already, this book will touch your heart. The author flawlessly achieves her aim of “evoking the many lessons of the June 2008 fire”, among them, “the effort and courage it takes just to pay attention.” Buddhist Zen teachings for everyday life abound in these pages. The invitation? to surrender to the idea that fire, in this human existence, is here to stay. For our five protagonists the inferno temporarily manifested as great fear and doubt. But it never seared their commitment, love and determination to do what their souls knew was the right thing to do, in that specific time and context. “Awakening too is on fire. it comes and goes.” The reader is introduced to the landscape of the valley, to the generous nature of the creek as protector of wildlife and humans alike, and to the wisdom of Zen masters such as Dōgen and Tassajara’s cofounder Suzuki Roshi. However, there’s never a moment when one loses track of the most intimate thoughts and the immense physical and emotional challenges the main characters faced. As they navigated their personal relationships, they were often called to make split-second decisions that would later prove to be of great consequential nature. Today, at Tassajara’s Zendo a +2,000-year-old Gandharan relic stills bears witness to the Bodhisattvas’ pledge of mindfulness. A tight daily schedule continues “releasing” practitioners to live in the moment of their assigned tasks. The Zen Mountain Center effortlessly thrives with lush promises of renewal, even as the scorching summer heat reminds those at the canyon that wildfires could at anytime pay another visit. Among the “fire monks”, this book introduces one to Mako. The now Abbot of San Francisco Zen Center, diligently documented (and preserved for posterity) the dangerous magnificence of the blaze. She recently expressed to me her hope that flames don’t come around again. But when she and the others extinguished them over fifteen years ago, they proved Suzuki Roshi’s teachings right: “It’s the effort that counts.” This book superbly spells out the enduring wonders of theirs.

At some point, though, it may be helpful to have a working understanding of some of Zen and Buddhism’s foundational ideas and influential people. When that time comes, give The Circle of the Way: A Concise History of Zen from the Buddha to the Modern World a try. And, just maybe, in this 2,000-ish year history you may find an introduction to something (Abhidharma, Yogacara) or someone (Dongshan Liangjie, Ruth Fuller Sasaki), that creates connections in your practice you didn’t even know could be there. As Barbara O’Brien observed when describing the resistance that some people have to some aspects of practice, “You never know what’s going to open the door.”

The history of Zen as told by Barbara O’Brien, a self-described “very slow [lay] Zen student,” is the messy, imperfect history of humans. In parts it reads like an epic Tolkien-worthy saga dipped in a Korean drama wrapped in Days of Our Lives. Across centuries of blood-thirsty warlords, rebellions, rivalries, social and political unrest, family squabbles, government mandates, and epic-level strife, somehow — remarkably — Buddhism and Zen practice has persisted through it all. While some of the details are lost to history, as O’Brien points out many of the ancient disputes are still relevant to us today whether or not we are aware of them. Maybe they can inform our present-day lives. For example, could the so-called epic Northern and Southern schools debate offer perspective on present day national political situations (looking at you, Democrats and Republicans)?

Barbara O’Brien also candidly addresses some of the surprising inconsistencies and seemingly factualized fictions in Buddhism and Zen, such as how the historical Buddha may be more of “a hypothesis than a person,” whether a single person named Bodhidharma really did come from the West, and how the lineage of the patriarchs was a 6th century invention by practioners in China rather than a reflection of historical fact. Does this suggest that all of Zen is an elaborate fiction in a complicated social and political landscape? Does it illustrate that Zen is a product of culture and/or somehow transcends culture? Importantly, how does knowing this context and navigating these questions impact your practice?

For me, O’Brien’s book opened more questions than it answered, which is my general experience of practice anyway. It pointed me to writings I’d never come across before, like the Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana, and illustrated the sometimes complicated relationship between governments and Zen. Does knowing that the military dictatorship (shogunate) in Japan ordered that Soto Zen use Dogen’s teachings as the basis of practice change how Dogen’s writings impact my practice? No, it doesn’t, but understanding how historical political interests shaped present-day practice has helped me see how this process may still be unfolding today. While knowing the history of Zen is not a prerequisite to embodied Zen practice, O’Brien’s introduction to so many previously unknown ancestors and the challenges they met inspires me to be a part of bringing this practice to the future. May this book inspire your practice as well. You can listen to the Q & A the All Beings Zen Sangha had with the author here.

at WorldCat.org

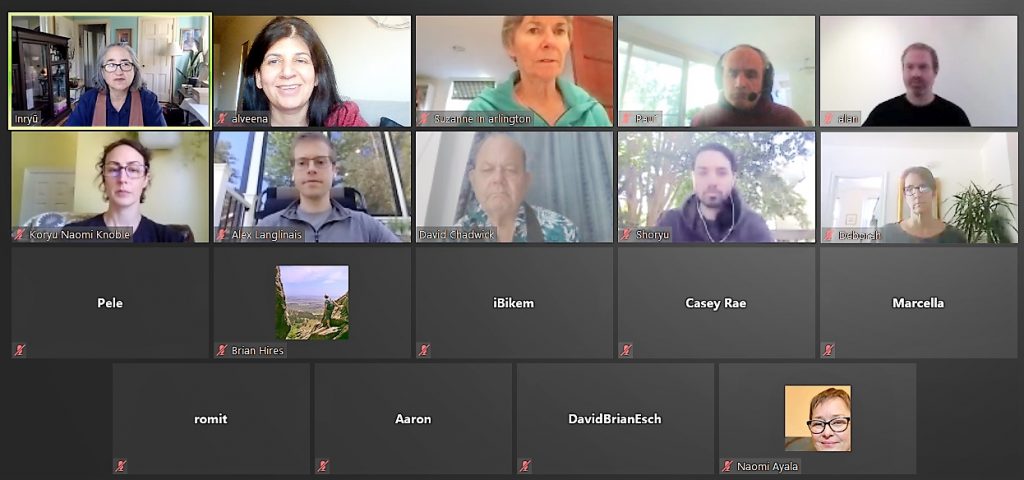

Above is a screen shot of a zoom conversation that ABZS had with the author David Chadwick (in the center of the image joining us from his home in Bali, Indonesia) on September 19, 2020. You can learn more about David Chadwick and see his amazing archive of information about Suzuki Roshi by going to this link.

Review by ShōRyū Christopher Leader

Zen Master Raven: The teachings of a Wise Old Bird / Robert Aitken/Published by Boston : Charles E. Tuttle ; Enfield : Airlift, 2002 and by Wisdom Publications, 2017

At WorldCat.org

* Quotations from Tenzo Kyōkun are drawn from How To Cook Your Life: From the Zen Kitchen to Enlightenment/Eihei Dōgen and Kōshō Uchiyama/Translated by Thomas Wright/Shambhala 2013.